Hey teacher, how do I type a hash(#)?

Introduction

I spent two and a half years in Rwanda as a volunteer IT educator with KOICA (Korea International Cooperation Agency), as an alternative to the mandatory Korean military service.

The quote above was the very first question I received from a student in my first C/C++ programming lecture, during the classic 'Hello World!' example. This course was for second-year IT majors at a college in Rwanda.

...and this, it turned out, was one of my better days.

But my keyboard does not have [#]!

Challenges (a.k.a. The Reality)

When another student shouted right after my short instructions on how to use the shift key, I realised that the student had a German keyboard. Some students even had Arabic keyboards!

But again, this was one of my better days – because, at least, the school had electricity that day.

Frequent Power Outages

How many people in developing countries have 24/7 access to electricity? Some things that are obvious to us are considered luxuries for people living in this part of the world. Teaching anything computer-related without power was a great challenge for me and my colleagues.

This fact extends to personal access to computers, not to mention an individual's ability to afford one. We can safely assume that the lecture hours are the only chance for students to use computers.

Power outages also cause maintenance issues. Due to the unstable electricity, computers have a significantly lower lifespan, forcing schools to spend more money on parts.

The Rainy Season

This may sound strange, but the weather was a great blocker for running courses, for two main reasons.

First, during the rain, it is extremely dangerous to move in Rwanda due to the high chance of lightning strikes. Also, one of the main affordable and reliable means of transportation is the moto-taxi, which cannot run in heavy rain. This means most students will not make it to school in such weather.

Another reason rain hinders a lecture is the tin roofs. Most Rwandan schools and houses are built with affordable tin roofs, which make a lot of noise during the rain. In a pouring rain, it is simply impossible to hear anything under such a roof.

The Language Barrier

Education in Rwanda after primary school is officially conducted in English. However, in rural areas where the average education rate is relatively low, it is realistically not possible to give lectures only in English.

On the other hand, there was no material on IT education written in the Kinyarwanda language, so it was a great challenge for us to prepare our own lecture materials.

Approach

It is obvious that we, as a group of volunteers, could not radically solve all the problems at once. We had to focus on what we could achieve within our service period.

Our primary goal (targeted for IT education volunteers) was very clear – to effectively teach students how to type. We simply could not move on to the next lecture without students being able to type!

We decided to make a typing practice software, and we defined three main approaches to help ourselves achieve the goal:

Localisation

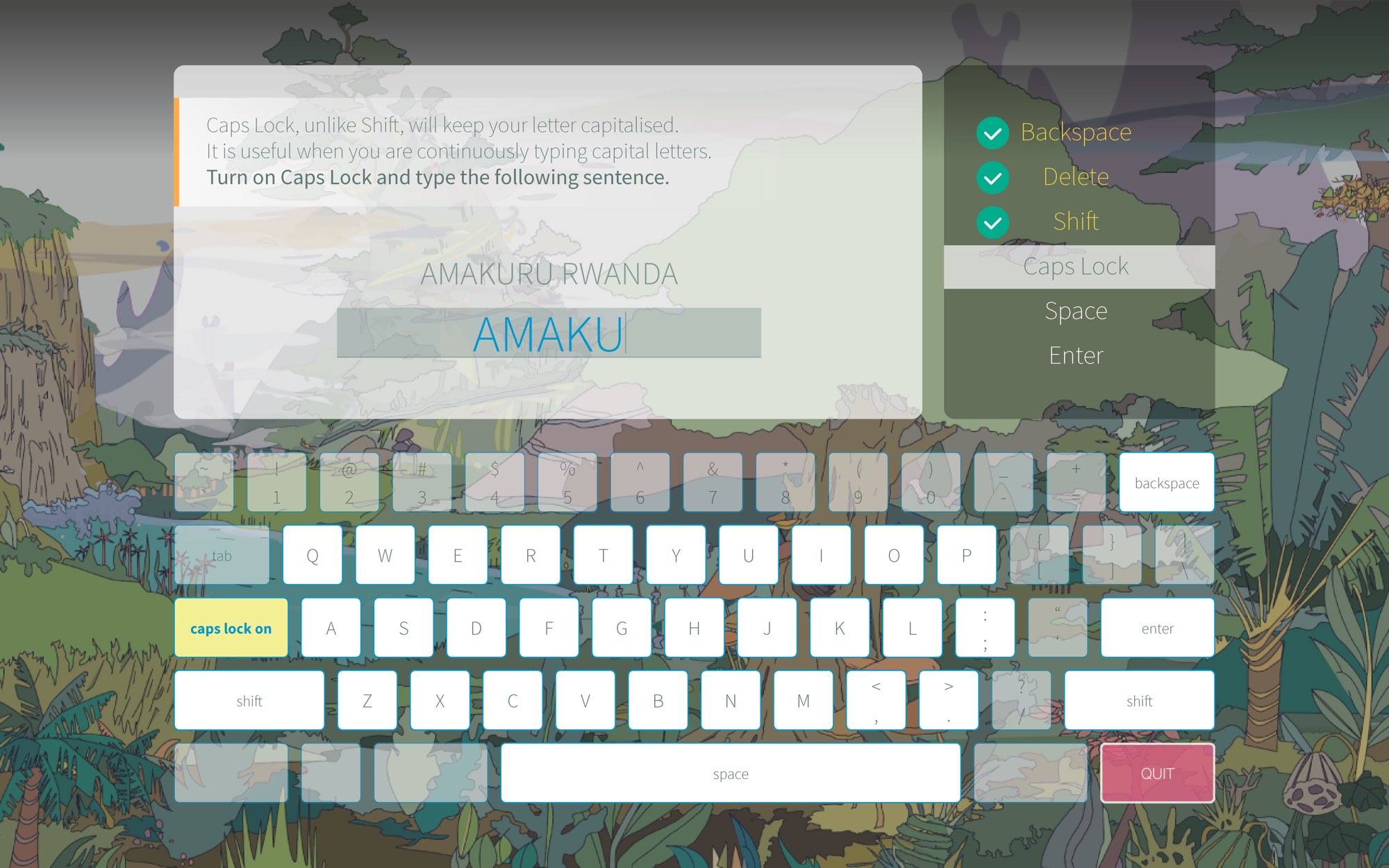

The main reason we decided to develop another typing practice software was because there was surprisingly no available multilingual solution. The whole point of this is to make educational material written in the Kinyarwanda language.

Playfulness

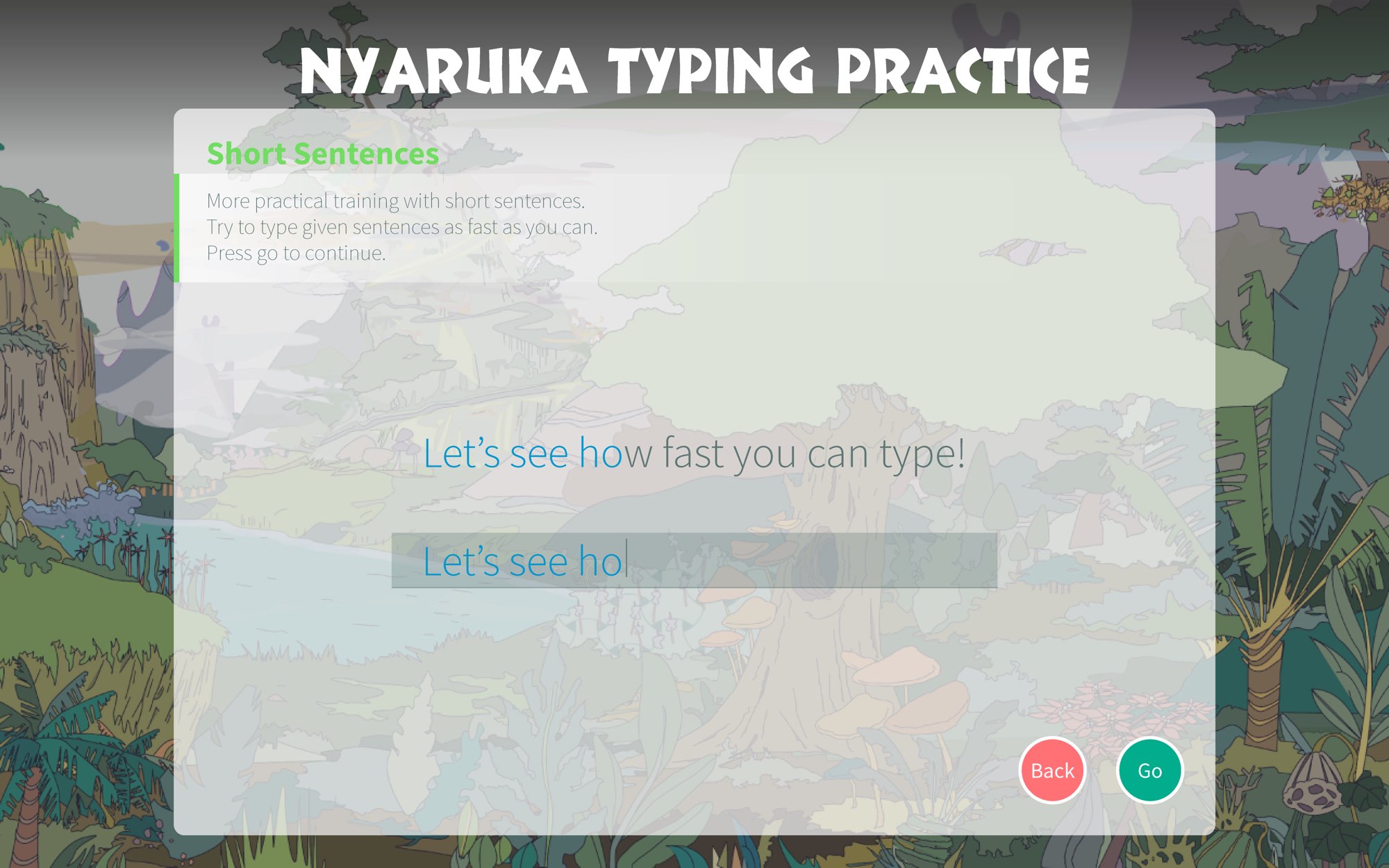

The software is mainly for teaching young students, and we also observed that many of them are often afraid to use a computer for the first time. We tried to make our software joyful so students can enjoy learning to type.

Literacy

Many students in Rwanda have limited access to books. Statistics show the literacy rate in Rwanda was below 70% in 2012. We thought we could help them read more by including literature for long-paragraph typing exercises.

Process

Once our approaches were defined, we quickly started to build the actual software, aiming for a quick proof-of-concept test.

The team focused on building a working prototype for the test phase. Meanwhile, we also gathered supporters from KOICA volunteers to arrange user-testing sessions together with the Rwanda Education Board.

User test

With the help of the Rwanda Education Board and participating schools, we were able to gather students to try our software. We wanted to test if students could follow the instructions, but more importantly, we wanted to know if this actually is an effective way of teaching. Below are our key findings.

Teaching methods

During our tests, it became clear that students had no problem following our software if we gave them clear instructions. This also meant proper training for teachers on utilising the software was necessary.

Missing features

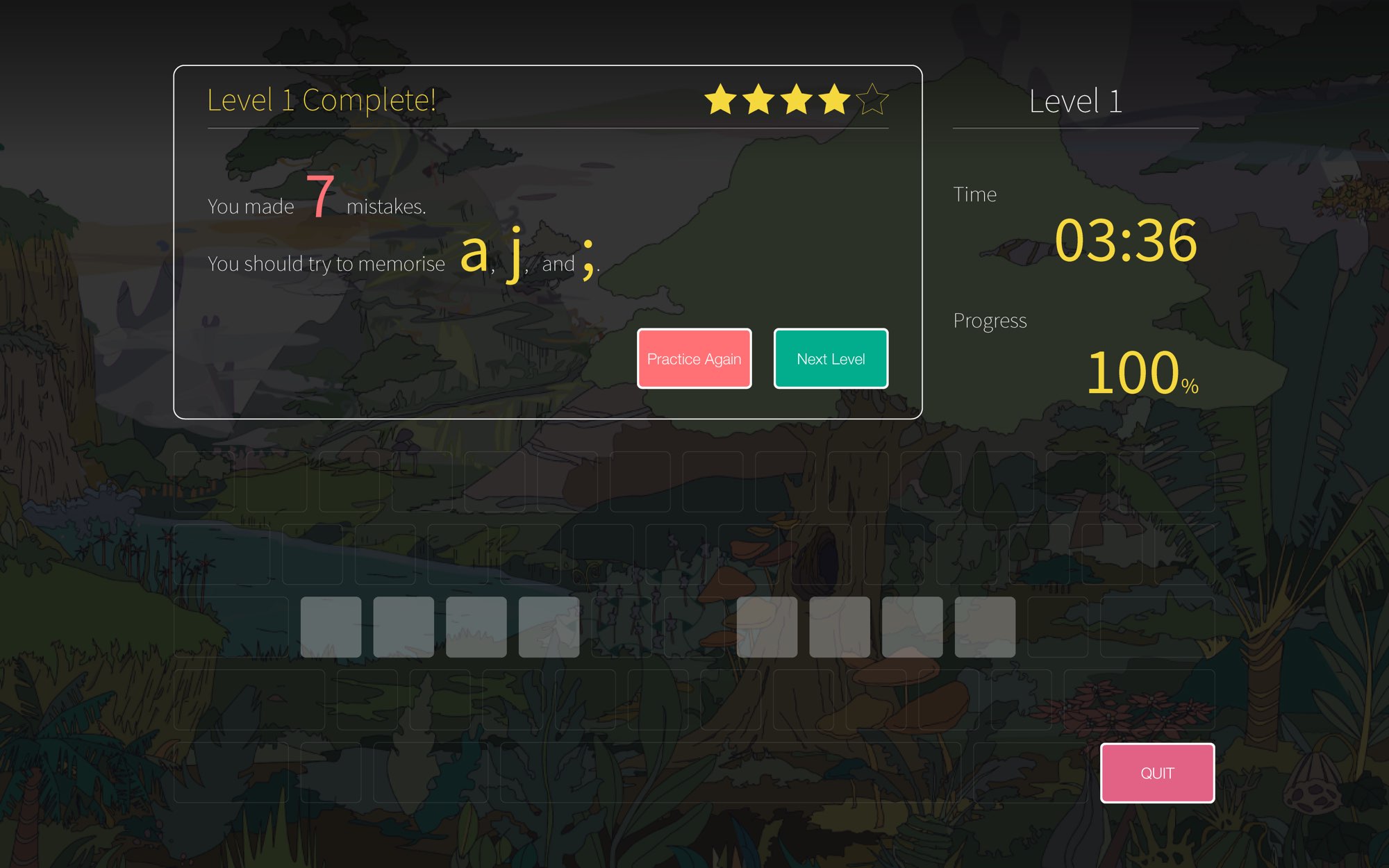

Our observations gave some inspiration for features as well. For example, we found out that students tended to keep their eyes on the on-screen keyboard, which prevented them from improving – so we implemented a feature to completely hide the keyboard.

Technical considerations

Although we were aware our software needed to run on low-end machines, there were still things we could not consider, for example, ultra-low resolution. Our test sessions helped us to ensure more coverage for schools.

Collaboration with Rwanda Education Board

One of the biggest challenges we had was the Kinyarwanda language. Also, gathering content for typing exercises was extremely difficult due to the lack of a digital database on literature as well as the rarity of Rwandan literature.

For this, we collaborated with the Rwanda Education Board to gather usable content. They were able to provide us with already existing course materials, and they offered to help us with translating English literature.

In addition, they agreed to include typing practice as an official curriculum for all Rwandan schools, which would significantly make distribution easier. To support the process, KOICA offered to sponsor software CD production and provide training for teachers.

Outcome

Based on the user test outcomes, we finalised our software with improved features and local content provided by the Rwanda Education Board. At the same time, we proceeded to organise teaching sessions to introduce it as well as train the first group of teachers and students.

Nyaruka /ˈɲaruka/ n. to be quick

The software

The name Nyaruka was suggested by the Rwanda Education Board, which – according to them – straightforwardly represents the purpose of “enhancing typing speed.”

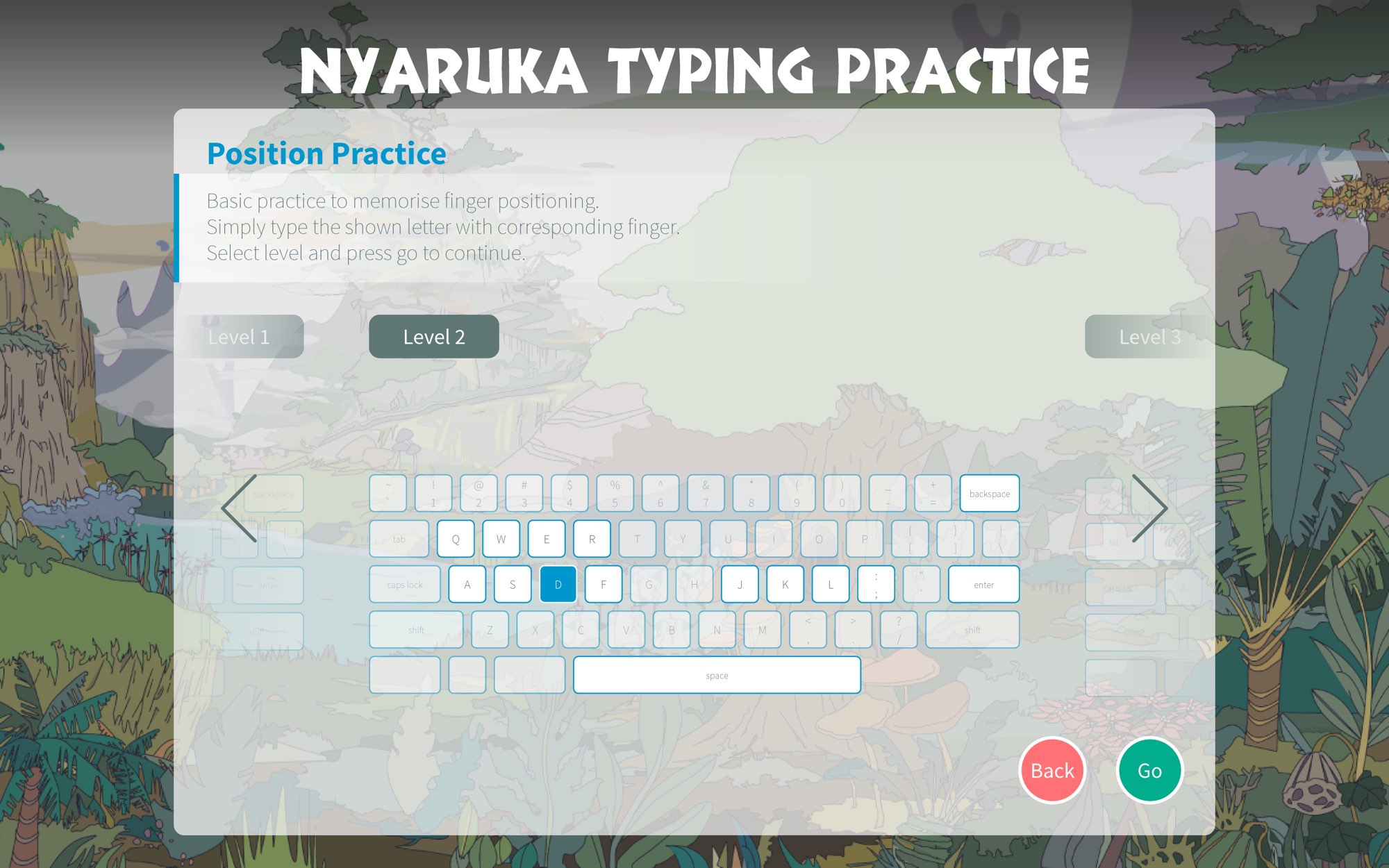

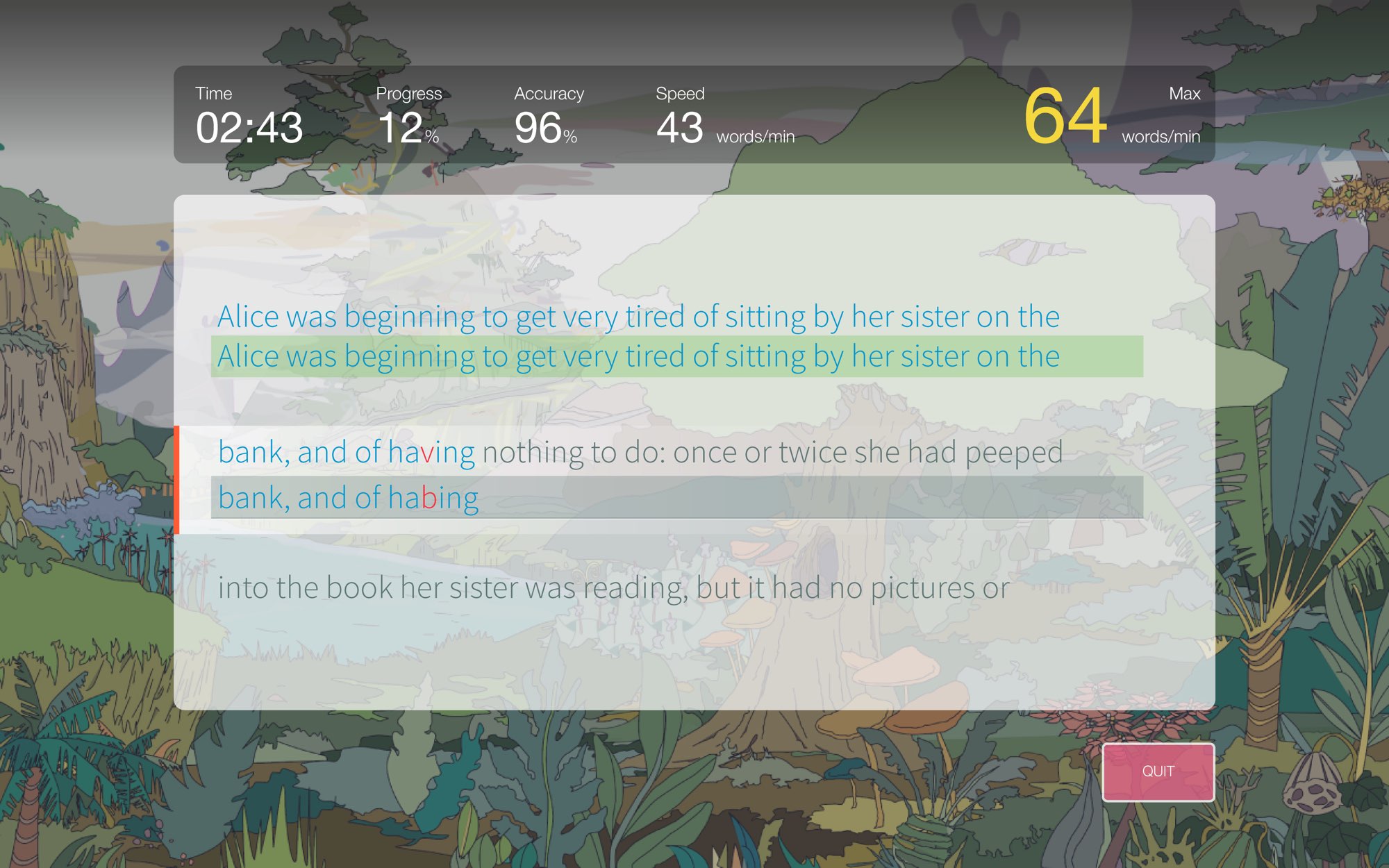

The structure of the program is similar to other existing typing practice software, with keyboard position training and various exercises ranging from single characters to long paragraphs.

We tried to gamify the learning process, hence the joyful design style with game-like interfaces. We found this very effective, as several people during showcase events challenged us to compete in typing speed. Interestingly, the gamifying process itself helped us to naturally come up with new evaluation criteria, such as frequently mistaken keys.

Applying to the field

After finalising our software, we actively sought opportunities to utilise it in actual teaching situations. While in bulk production, it was pre-distributed to KOICA volunteers who could directly apply it in their teaching.

We were also invited to the Techkobwa camp – Tech-girl camp – organised by the Peace Corps and Michigan State University as part of a women's empowerment programme. Together with their volunteers, we gave effective typing lessons to Rwandan girls using our software, along with other general IT courses.

It was a great opportunity to test, develop, and share teaching methods with education experts from the field, especially because many of the KOICA volunteers did not have any pedagogical knowledge. We later shared our learnings with the KOICA community to apply new methods in our teaching. A detailed evaluation report on the Techkobwa camp can be found here.

Sorry, we need to remove the content about the Genocide.

The Last-Moment Failure

Everything seemed to be going so well, until the very last moment. And there was nothing we could do about it.

The Rwanda Education Board informed KOICA shortly after the production of the software CDs that they could not distribute them until we fixed our content. We tried to triple-check our content together with the board members before production, but unfortunately, this nevertheless happened.

Things got really tricky as KOICA had already spent its entire budget to produce the CDs, and to make things worse, the team's service period was almost ending. If things could not be solved within a few weeks, there would be nothing we could do.

The Rwanda Education Board and KOICA had several meetings to seek solutions, but sadly the conflict only worsened into political arguments. Eventually, the distribution was postponed indefinitely, with neither side following up to this day.

Learnings and Next Steps

A project can nevertheless fail – the team learnt it the hard way. Although we, as experienced volunteers in the actual fields, were clearly aware that anything unexpected could happen, it was very hard for us to accept the result. The reason behind our failure was completely out of our control, and there was nothing we could do about it – a painful but lifetime lesson.

How can we teach IT without any digital tools?

Despite the unsatisfactory result, like any other project, our journey gave us priceless learnings. I personally found the collaboration with the Peace Corps and Michigan State University really opened up my eyes.

As a computer education volunteer coming from a non-teaching background, I have never thought about teaching the digital world without plugs. However, what those education experts demonstrated in the camp made me realise how creative teaching could be and also how unprepared I was in giving such an education to others.

Just like preparing design workshops, those volunteers prepared a number of activities students could easily do without any power – for example, playing with binaries using simple black-and-white cards!

Applying teaching methods for and with typing practice

Such an experience also made me wonder if there would be more effective ways of teaching how to type. None of the team had any knowledge in pedagogy, nor did we learn to type with a software like this.

I recently (2019) had a good discussion with a friend regarding this project, as I am currently planning to re-develop the software. They suggested I focus on utilising the software in teaching rather than focusing on the typing itself, as most of us learnt to type naturally rather than by practising with a software.

Inspired by this, and also looking back on one of our first aims to increase literacy, I hope to re-launch this project in open source and suggest a new school curriculum for developing countries, in which students have more chances to read and type.